On the other hand, for those of you who are simply brass, hard-headed fools like myself, there is always the comforting option of surgery...

POP! Everyone within twenty feet of me heard it. It sounded like the crackling-snap of bubble wrap, only much louder. I was on a road trip: Boulder, Colorado. I had been trying to keep up with two of the country's top climbers (name dropping: Daniel Woods and Paul Robinson) for the past seven days. Needless to say, my attempts were futile considering the fact that I do not on-sight V11 (little, skinny-ass freakin’ punks). In either case, I had been pushing my limits without rest, ignoring “minor” pains, and climbing with utter disregard for my body’s blatant caveats.

The popping sound ended up being the complete rupture of an A2 pulley, the elastic-like band that keeps the flexor tendon attached to the bone. This tear was more than just the result of a stressful climbing week, but more of a culmination of over-training and inadequate rest. For six months prior to the trip, I had ignored the exponentially growing pain in the upper region of my palm at the base of my ring finger. The A2 pulley is arguably the most commonly injured ligament in climbing and I became yet another tally in Eric Horst’s statistical chapter of unlucky climbers.

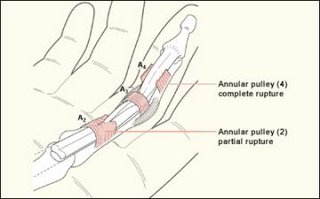

The diagram below illustrates some of the most problematic areas in terms of critical stress points. The partially torn A2 pulley demonstrates the precise location of my re-occuring pain, the genesis and primary catalyst for the resultant rupture as exhibited later on. It is also important to be aware that no amount of rest or icing therapy would have rectified such a tear because tendons and ligaments are non-vascular tissues, which means that they are not supplied with blood in the same way that muscles are. Simply stated, pulleys never actually "heal" once torn.

Had I immediately stopped climbing upon the first indication of pain and rested until all signs dissipated, I would have most likely avoided such a devastating injury. There are a million different stretches, ways to tape your fingers, and voodoo rubbing-gels to supposedly prevent such injuries, but they pale in comparison to a climber who simply listens to his or her own body. The brilliant person who came up with the old proverb, "No pain, no gain," should be taught a serious lesson.

Therefore, instead of going to the gym for the 6th time in one week in order to impress your buddy on a new, plastic “V- Forehead Vein Popper,” grab a nice garden salad and some soy milk and watch a movie for the afternoon. Although, personally I would substitute the garden salad with a large Dominos pizza and the soy milk with a Colt 45. Either way, you are allowing your body to rest, promoting necessary re-growth and development, the most critical component contributing to the infinite improvement of any climber.

Therefore, instead of going to the gym for the 6th time in one week in order to impress your buddy on a new, plastic “V- Forehead Vein Popper,” grab a nice garden salad and some soy milk and watch a movie for the afternoon. Although, personally I would substitute the garden salad with a large Dominos pizza and the soy milk with a Colt 45. Either way, you are allowing your body to rest, promoting necessary re-growth and development, the most critical component contributing to the infinite improvement of any climber.Unfortunately, I pushed my body to the point at which it could no longer efficiently regenerate. Consequently, after a quick flight home to Boston, away from a seemingly endless abundance of projects in the West, I found myself in Doctor Shilmer's office, a highly esteemed surgeon at Newton-Wellesley hospital.

The consultation went like this:

"So, Mr.Wetmore, you have managed to completely tear through the A2 pulley on your ring finger. I usually only see these types of injuries in people who check the sharpness of a chainsaw wih their fingers or attempt to fix the moving parts of a snowblower with their bare hands. You managed to do this all on your own, eh?"

"Um...yeah." I muttered, wondering if I was supposed to be pleased with myself or if he was going to give me a gold star, maybe even a lolli-pop.

"Luckily, we have designed plastic rings you can slide over the outside of your finger to act as a prosthetic pulley," the surgeon shot-off with a beaming smile.

This ridiculous offer of hope made me want to vomit and throw myself out the window. A ring! A goddamn ring! I'd barely be able to hold a plastic fork for my mac-and-cheese without my tendon bowstringing into my face, no less crank my 170 pound frame up a half-pad crimp. I remained calm and continued with whatever composure I could muster.

"I heard you can do surgery, ya know...like...rebuild the ligament so I can climb again. Can we just do that?" I asked red-faced and vibrating with nerves.

"Of course. That would be ideal for maximum strength, but there is no guarantee you will have full movement in your..."

I cut him off. As far as I was concerned, surgery was my only chance. "Let's do it. Tomorow? When can we get this done?"

Four days later, in an airy, robbin-blue gown (a bit too "airy" if you ask me), I was slowly drifting off into a soft, black abyss under the inescapable submission of a Demerol-Morphine cocktail. My surgeon and his possy of green-clad nurses prepared me for surgery as I passed out under the bright, white lights above.

My father was in the room right before I fell asleep. He said I had a moment of reflection right before I went under:

After gently waving over the surgeon, I drunkedly whispered into his ear, attempting to grab his elbow. My tone was so overly austere that the absurdity of my statement seemed null. Who tells an experienced surgeon what to do? I apparently did.

"Doctor Shilmer, just between you and I, sir, do you think you could double-wrap my finger, please? Its gotta be strong for climbing...one wrap just won't...climbing is..."

He turned to my father with a wry smile, rolling his eyes in amusement. But he had heard me. He increased the intravenous drug intake and I was out.

"Will do Dave, will do."

After undergoing reconstructive surgery on my A2 pulley, I spent two months in a cast. The surgeon essentially cut-out a six inch strip of ligament from my wrist and double-wrapped it around the base of my ring finger. He had honestly never completed a "double-wrap procedure" before. Needless to say, I now have an extremely apparent lump of tissue under the skin of my ring finger. Perfect!

Two months went by agonizingly slow. With the cast finally off, I spent another two months gradually easing back into climbing, cranking "sick" slab problems and jug-hauling on vertical walls. Jesus H. Christ. Thus, a total of four months later after the fatal snap, I am back at full-strength, pulling into holds as if my life depended on it.

As a result of such injuries, I have vastly changed my climbing style from less of a choppy, dynamic fight to more of a flowing, controlled pull in order to minimize the shock load on vulnerable pulleys and tendons. As a new rule, I rest for two days after every hard day and generally throw my hands in a bowl of ice after every session. So far, no pain.

In fact, last week I strolled out of isolation, past Mr. Obe Carrion, to throw myself at the "Mens Pro Finals" problems. Over the blarring techno music and screaming crowd of climbing fanatics, I could hear the all-too-familiar reassurance of that sharp, Russian voice.

Vasya, my best friend and most fiercely competitive adversary, shouted from the corner of isolation.

"Hey buddy! It's time to crush! I'll be right behind ya...watch out!" he cracked with a wise, beaming smile.

Quickly glancing down at my new finger, I flashed a smile, chaulked up, and reeled into the starting jugs.

I was back where I belonged.

Defeat is not defeat unless accepted as a reality in your

own mind. - Bruce Lee